Shoulder Pain: Pt 1

This Month’s Focus:

Sucky Shoulders

This month, I’ll be sharing some of my own shoulder challenges and goals, as well as some specific tips from trainers and therapists to decrease pain and increase strength/range of motion in your shoulders. If you’re a bartender, a tattoo artist, a hand-stand master, or anyone that experiences regular shoulder pain, follow my Instagram feed.

The fact is the shoulder joint can be a beautiful work of art, or it can be a piece of crap. What we gain in versatility and range of motion we give up in stability, making our shoulders more susceptible to injury than almost all the joints in our bodies. It’s a complicated region of the body, so I’ll be breaking this post into two parts to devote more time to what couples your shoulder together, and what ultimately breaks down there.

Join Me:

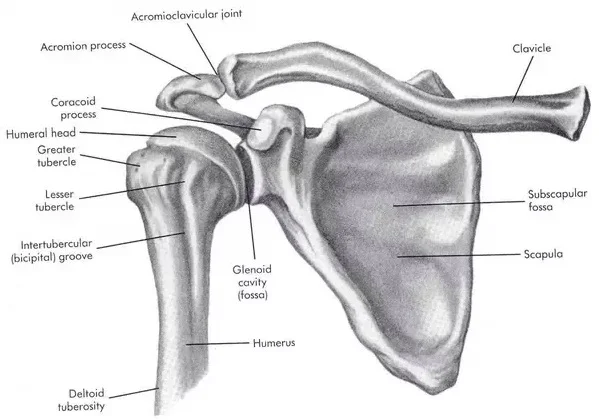

Your handy-dandy arms, which move almost without your thinking (carrying bags, shaking cocktails, reaching for your phone, flipping off the drivers around you), attach to your body at only one real joint - the ball-and-socket glenohumeral joint, which is a shallow recess on your scapula.

Seriously? That’s all we get? WTF.

That’s it. The only spot. Every other thing preventing your arms from falling off your body are tendons, ligaments, and muscle. The scapula that your arm is dangling off of attaches precariously to your collarbone, and slides around on the back of your ribs. It’s not a fantastically designed mechanism for absorbing force, which is why clavicles are some of the most commonly fractured bones in our bodies. Remember that the next time you’re swinging a 40 pound work bag off one arm.

Your shoulder joint isn’t completely devoid of reinforcement, however - it’s wrapped and bound by a lot of masking tape in the form of fascia, ligaments, tendons, and muscle. But masking tape wears down with regular abuse, and can’t help stabilize you against sudden impacts or pulls. The shape of the humeral head as it rotates around your joint means it’s least stable (and most likely to dislocate) when your arm is extended and heavily rotated out. Most people think of dislocations as just a sports risk, but they’re also common in motor vehicle collisions and hard slips/falls.

Dislocations can occur forwards, backwards, and downwards, with forwards being the most common. Once you’ve dislocated or subluxed your shoulder, it’s more prone to popping out again. Oh boy!

Move Me:

The main movers and shakers of your shoulder are the four rotator cuff muscles : supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor. Together, they swing your arm and swivel your scapula in various and precise ways so you can both reach for your iPhone and juggle bowling pins at the same time (if you’re in for that sort of thing). They’re commonly stressed with our day-to-day grind of arm use, and especially prone to overuse injuries. This happens for various reasons, but a major one is that we tend to over-abuse some in this group and neglect to stretch/strengthen others.

Some other main shoulder players are your deltoid, pectoralis (major and minor), latissimus, rhomboid, and serratus anterior muscles. There are a few arm specific movers as well, but I’ll leave those for another day.

That’s it for now! I’ll post Part II next week, after you’ve had some time to mull this all over. With that post, we’ll talk common shoulder injuries (especially as they relate to specific jobs), and ways to stretch/strengthen that area of your body. See you then!